Beyond Creating Content: We Can Influence the User’s Experience

You have created a content strategy targeted at specific users and their unique needs. You have helped improve your products through usability testing. So what more can you do to make a difference for your product, team, or business? You can influence the overall user experience of your product. You can use your position and knowledge about the user’s needs to help ensure the success of new features and changes to existing ones. The tools are simple: user profiles, journey maps, usability tests, your knowledge, and your confidence. You can become an advocate for the user.

As technical communicators, we have the basic skills to become user advocates who influence the user’s experience for our products. We think strategically to organize content according to the user’s needs. We ensure that the user has the right information at the right time. We are not invested in the internal functionality of the product or how the code is written. Rather, we view and often use the product from the user’s perspective. To become a user advocate we simply need a good understanding of the methods for improving user experience, as well as the confidence to use our skills and knowledge at the right stages of the design process.

User Experience is More Than Usability

To the newcomer, the concepts of usability and user experience might seem synonymous. However, usability is a component of the overall user experience. Usability expert Jakob Nielsen defines usability as a quality attribute that assesses how easy user interfaces are to use (Nielsen, 2009). To assess usability, we look at task-based interactions: what the user is doing and how the user does the task. We want to reduce the steps in a task or ensure that the tasks can be performed easily and intuitively. User experience focuses on the user’s emotional connection to the task. We ask: Why is the task meaningful for the user? How does the user feel when interacting with the product? If the user performs a required task every day to get a job done and nothing more, then the user likely sees the task as routine and boring. If that same task is easy to perform, it might have good usability but very poor user experience.

In addition to usability, user experience includes the following elements:

- Branding, which defines the targeted users.

- Functionality, such as the product architecture, design, and interface. This element ensures that the product does what it is designed to do.

- Content, which includes your content strategies, interface labeling, and messaging.

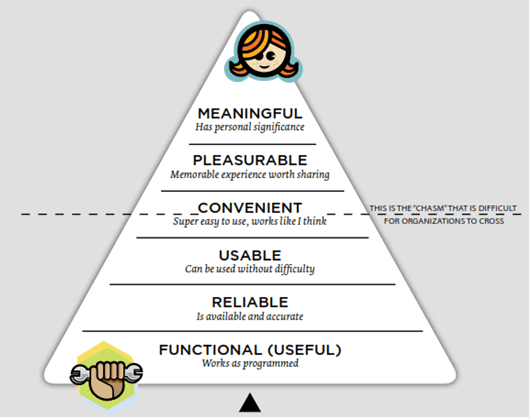

Figure 1 provides a great example of the user experience elements according to Stephen P. Anderson. At the bottom are the basic requirements that your product should meet. The demarcation line running through “Convenient” shows that this need is both a basic need and an element that can elevate the user experience.

Figure 1. Hierarchy of User Experience Needs (Anderson, 2011)

User Experience Requires Knowing Your Users

It seems obvious to state that the most important element in user experience is the user. (Yet, I stated it.) Before the development team starts writing code, we should start thinking and acting on the user’s behalf. Thus, we need a strong understanding of our users. Google states this concept best in their belief “focus on the user and all else will follow” (Ten Things, n.d., para. 2). To start, we gather information about our users and delve beneath the surface of their answers. Then we learn about their needs, pain points, and behaviors. Once we know these facts about our users, we can create user profiles and user personas to help our development team focus on each user.

The best ways to learn about your users are personal interviews and observing users at work. However, content writers often do not have direct access to users. In these cases, we can interview subject matter experts (SMEs) who do have regular contact with users. You can gather feedback from technical support, product managers, field sales, field engineers, and in-house sales staff. Depending on your product, you might want to get demographics about your users, such as age, experience, job tasks, job titles, and goals. During the interview, ask open-ended questions that allow the interviewee to expand on the topic. Schlomo Golz (2014) provides a great list of questions, such as

- How do you do [a certain task]?

- How long does this task typically take?

- Where would you start?

- What would you do next?

- What are the most difficult, challenging, annoying, or frustrating aspects of your job?

You can also review web analytics to determine areas where users might pause, ask for help, or even abandon a difficult task. These types of analytics can help you identify user pain points, which represent those frustrating or difficult aspects of the user’s tasks or the activities for which the user does not have a useful tool. At the same time, question all assumptions: yours, your team’s, and even those of the user. When you receive an answer such as “we always do it this way,” try asking either of the following questions:

- Why did we choose to solve the problem in this way?

- Could we have done it in a different, better, or more remarkable way?

At the very least you need to know what users do, how they do it, and why they do it.

Once you have learned as much as you can about your users, you can create user profiles and personas. A user profile represents a group of users with common characteristics, goals, and behaviors. It provides the facts and figures about this group. Basically, the user profile explains what the user does and how the user does it. Depending on the complexity of your product, you might have a single profile or several. To ensure you have identified the right user groups, look at each task, feature, and solution that your product provides; then determine which profile applies to that activity. Next, create a user persona for each user profile. The user persona represents a virtual user, complete with name, picture, and background story. The persona serves as an archetype, based on the profile data. It describes that user’s skills, needs, behaviors, goals, motives, and interactions with other user personas. It explains why the user does what he does and why she chooses how to do it a certain way. The persona breathes life into the facts and figures of the user profile. Because the user persona serves as the “voice of the user” (Ilama, 2015), you can treat that persona as a human when interacting with your development team. Tell stories about what the persona does and why. The more you tell stories and talk about the persona, the more your team can empathize with the users that persona represents. Empathy enables your team to become that user. Then you can add journey maps and usability testing to help your user advocacy program.

Map The User’s Journey

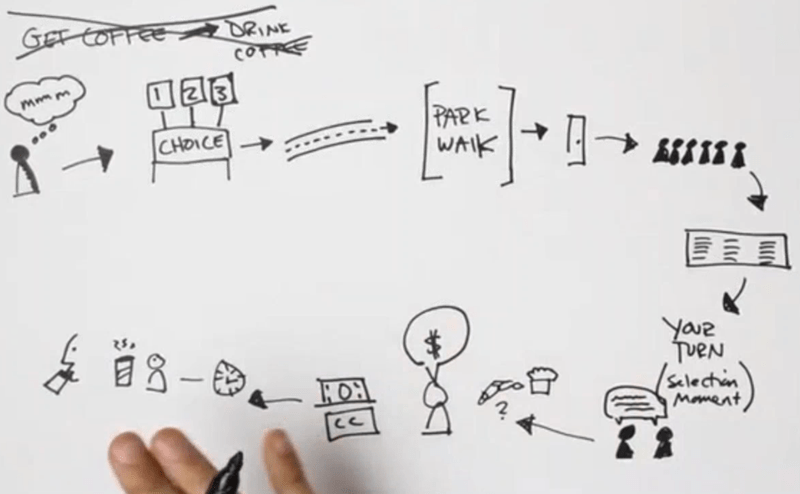

To create a great user experience, walk in your user’s shoes. A user persona encourages your team to say, “I’m going to log in as Andrew the Administrator and try to complete this task his way.” To help your team in this endeavor, map the user’s journey. A journey map help us understand the user’s experience for a single process or a very complex one. For example, Figure 2 shows the process for purchasing a cup of coffee (Journey, 2013), starting with where to get the coffee and ending with the first sip.

Figure 2. Sample Journey Map

Based on scenarios or tasks, the map allows you to group user activities by the solutions that they provide. You can then organize the overall process, plan for future solutions or enhancements, and set priorities for competing deliverables. You can also use the journey map to organize content within the user interface because it helps you identify the information and content that the user needs at each stage of the journey. The journey map can identify the user’s pain points. It also helps you discover what you might have missed or where you have added too much to the process or user interface.

To create a journey map, select the feature, task, or solution that your product provides for a particular persona. Walk through the activity stage by stage. For each stage, describe the user’s actions, thoughts, feelings, and experience. You should identify the outcome or result that the user expects for that stage. You might also want to note whether a stage can be skipped, when and why.

You can create a journey map at any time. In a best case scenario, your entire development team should participate in the process. Doing so allows the team to not only improve the design through questions and clarifications, but also have the same view of the mapped process, which can reduce issues when coding begins. If the whole team is involved, you should create the map at the planning stage of the project. However, you can also create the map during the design phase to ensure you have the right elements in the user interface at the right time. If your development team is not ready for journey mapping, you can create a journey map on your own at any point during the release. After a release, you can use the map to track whether the features the team created actually match what the user needs to do.

Also, you do not need a special tool or software to create the journey map. You can use Post-it notes, a white board, Microsoft Excel, or PowerPoint. Basically, use any method that enables you to describe and share the user’s journey to others. Because the journey map describes the user’s thoughts, feelings, and expectations, it helps you empathize with that user, which helps improve user experience.

Perform Usability Tests

You can improve the user’s experience with usability tests that do not require a large budget or professional usability experts. These simple, do-it-yourself usability tests have a common set of rules (Nielsen, 2012) where test participants:

- Represent a persona

- Perform representative taskswith the design

- Do all the talking

You should perform the tests early in the development process so you can identify the most serious issues before your team has gotten too far along in the code. For testing, you can use wireframes, existing code, or paper prototypes. In Rocket Surgery Made Easy (2009), Steve Krug outlines the methodology for performing DIY usability tests. With a little practice anyone can use Krug’s method. You need a test moderator, three test participants, and a note taker. In a separate room, place all the stakeholders for the project so they can observe the tests. Each participant performs one or several tasks, but no more than can be performed in about 45 minutes. The moderator encourages the participant to speak aloud to ensure that the observers and note taker capture the user’s thoughts and feelings throughout the test. After the third participant completes the test, gather the stakeholders in a room (or conference call) for a debriefing. Identify the main pain points that the participants encountered. As Krug recommends, focus ruthlessly on a small number of the most important problems. You do not need to discuss the methods for resolving the issues or why the issues occurred. Save those discussions for another time rather than allowing the debriefing to get sidetracked.

These DIY usability tests can help you improve the user interface, identify the most serious usability issues early enough to make changes, and begin user-centered design practices. When the stakeholders observe users struggling, the DIY tests help the entire team realize that user experience is everyone’s responsibility.

Become a User Advocate

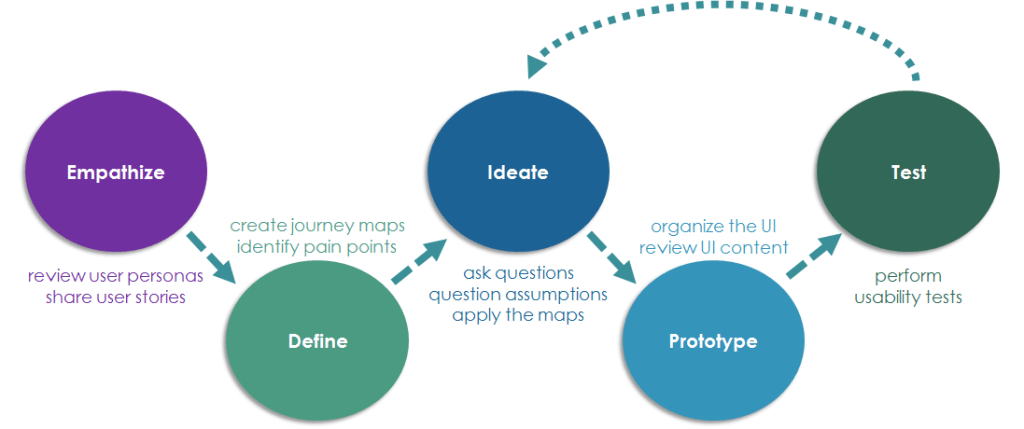

Figure 3 is based on the design process model created by Effective UI. At the Empathize stage, you create or update user profiles and personas, share stories about those users, and encourage your team to think like those users. The Ideate stage allows the team to plan methods for satisfying customer’s needs and resolving pain points. This is where you apply what you learned from the journey maps. If you have multiple solutions, perform quick usability tests to see which might be the best course. During the Prototype stage, you can review the user interface and organization of the user activities. Finally, in the Test stage, perform the DIY usability tests.

Figure 3. Applying UX Methods to Stages of Development

The model shows that you can influence the user experience at all stages of the design and development process – even when you don’t have a formal budget for user experience. Remember, your advocacy for user experience starts with sharing stories about users so the team will view the persona as real person. In doing so, you help your team make the product meaningful and pleasurable to use.

Resources

- Garret, Jesse James. The Elements of User Experience: User-Centered Design for the Web and Beyond (2nd Edition) (Voices That Matter). (New Riders) 2010. http://www.jjg.net/elements/

- O’Conner, Kevin. “Personas: The Foundation of a Great User Experience.” UX Magazine 640 (March 2011). https://uxmag.com/articles/personas-the-foundation-of-a-great-user-experience

- User Persona Creator. (n.d.) Extensio: https://xtensio.com/user-persona/

- Introduction to UX (October 2015). EffectiveUI. Retrieved from SlideShare: http://www.slideshare.net/effectiveui/introduction-to-ux?qid=4b66b853-9a9e-48fc-9740-a4ec76c8a971&v=&b=&from_search=9

References

- Anderson, Stephen P. Seductive Interaction Design: Creating Playful, Fun, and Effective User Experiences (Voices That Matter). (New Riders) 2011. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U-SNVLGBh5o

- Ten Things We Know To Be True. (n.d.). Google Company > What We Believe: https://www.google.com/about/company/philosophy/

- Ilama, Eeva. “Creating Personas.” UX Booth (9 June 2015). http://www.uxbooth.com/articles/creating-personas/

- Schlomo Golz. “A Closer Look At Personas: A Guide to Developing The Right Ones (Part 2).” Smashing Magazine (13 August 2014). https://www.smashingmagazine.com/2014/08/a-closer-look-at-personas-part-2

- Journey Map (4 November 2013). Stanford d.school: https://vimeo.com/78554759

- Nielsen, Jakob. “Usability 101: Introduction to Usability.” Nielsen Norman Group (4 January 2012). https://www.nngroup.com/articles/usability-101-introduction-to-usability/

- Krug, Steve. Rocket Surgery Made Easy: The Do-It-Yourself Guide to Finding and Fixing Usability Problems (New Riders) 2009. http://www.sensible.com/rsme.html